The quirks and performance of java arrays

Why a blog about the performance of arrays in java? They are old-school. Does anyone really need them?

The only (active) memory I have of seeing arrays in an actual codebase was in a situation where ideally you’d used multiple return types (like in Python) or first-class tuples (like in rust). Please don’t return multiple objects in an Object[].

What made you write this then?

Several reasons, one of which is a recent blog from oracle called Inside the JVM: Arrays and how they differ from other objects which was disappointing because it failed to reveal any useful new information. This puzzler is whacky though!

And, I had just written a blog post for my company site (in Dutch) about arrays. So I am all into them. This, by the way is the English translation of that post.

A little while ago I stumbled over the ghastlily poor performance of java.lang.reflect.Array. That started the whole thing. See here. I wanted to create a better alternative (but I haven’t progressed much though).

Arrays haven’t changed much (at all?) since java 1.0. Makes sense for backwards compatibility. And java in those days was somewhat weird (still is), or should I say: C-like. Look at this for example:

3 ways to instantiate multi-dimensional arrays

int[][] array = new int[3][2];// ok..int[] array[] = new int[2][2];// reminding of C pointer notationsint[][] array = new int[5][];// WTF?

What does option #3 even mean?

And how can this not give an IndexOutOfBoundsException?

1

2

String[][][] array = new String[1][1];

array[0] = new String[2];

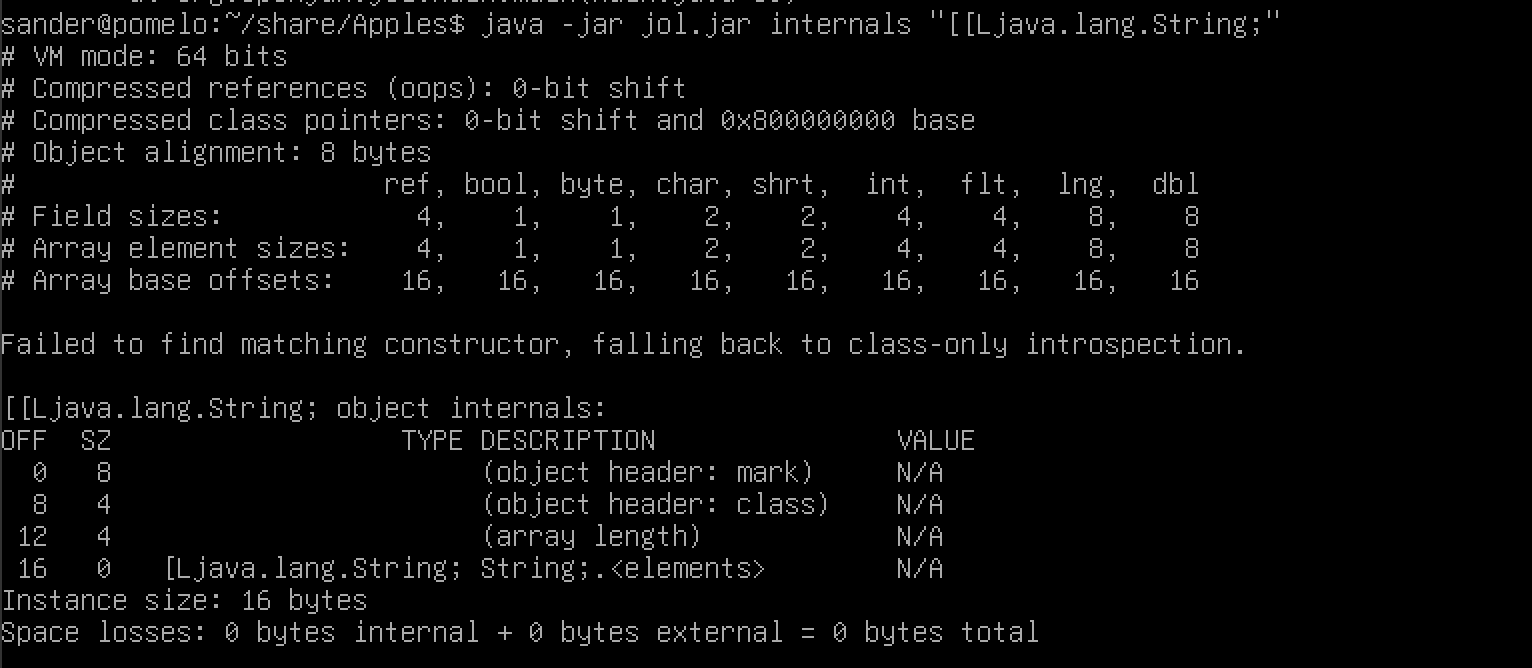

I couldn’t google the answer straightaway, so I turned to Jol to find out more. NB. Jol does not work really well on macos (dunno about windows), so ran it in a linux vm and saw the following:

Jol is a tool to investigate the memory internals of java objects. For a 2-dimensional String array you’d have to do this:

1

java -jar jol-cli.jar internals "[[Ljava.lang.String;"

BTW, notice the weird notation! I knew

[[Land;. If you look at bytecode, this is all over the place.Lindicates an object (as opposed to the primitives as inIfor ints) and[[is indeed an array of two dimensions. So those are the bytecode notations, but internally it also uses/whereas here it’s the.again. It’s confusing, but it turns out this is just the way thatClass.forNamewants it (if you need to need a Class object of that type). So there’s a thing I didn’t know.

Then it dawned on me. The phrase array of arrays means that the outer array really doesn’t care about the lengths of the inner ones. The only thing the outer array knows is its own length.

So String[1][1] is in fact String[1][]. Every element in the outer array is a 1-dimensional array, of any length! No runtime bounds checks here (C-like!). Of course once the inner array is initialized, there are checks again.

There are no true multi-dimensional arrays in Java, just arrays of arrays. This is why int[][] is a subclass of Object[]. If you need a large multi-dimensional int[] in Java, it is a bit more efficient to allocate a large int[] and calculate the offset yourself. However, make sure to, if possible, navigate the int[] in such a way that 64 bytes at a time can be read. That is a lot more efficient than jumping around. Heinz Kabutz

‘Jumping around’ is not efficient because it hinders CPU caching and prefetching. Random Access Memory is sloow! It’s thanks to the L1/2/3 caches that processors can actually show off their speed while dealing with memory. They fetch more than needed at the time and cache it for future reads. The effect of this amplified when the CPU can also predict your next move read. So the way you read and write an array matters.

But what performance gain can you actually achieve?

This question tripped me and I fell down the rabbithole of microbenchmarking. I learnt a lot more about JMH, but in the end I discarded all the measurements from my Mac M2 max and reran them on a standard Amazon linux AMI. The results were more in line with what I read elsewhere. It’s also more generalisable in the sense that server applications rarely run on high-end laptop architectures. Most of the time, my laptop showed a less prominent effect of caching.

Benchmarking with JMH

Your friend, the JIT compiler becomes your adversary once you get into benchmarking. Initially I glowed observing a performance difference of 1342%, but that had more to do with unwanted removal of dead code, than the actual truth. Something to be very aware of.

Also, testing your benchmarks makes sense. Verify you expectations of the actual functionality, to avoid the wrong conclusions about performance. Seems obvious but yeah, somebody had to point me to a mistake in my code…

This is what I ended up with

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

@Benchmark

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.AverageTime)

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.NANOSECONDS)

public long classicArrayGetTDLR() {

long t = 0;

for (int r = 0; r < ROWS; r++) {

for (int c = 0; c < COLS; c++) {

t += intArray[r][c];

}

}

return t;

}

TDLR stands for Top Down (outer loop), then Left Right. This order means that the code traverses row by row, which is good, because the memory is layed out like this. LRTD on the other hand takes one column after another. This will result in cache misses most of the time.

| Benchmark | Mode | Cnt | Score | Error | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| classic2DArrayGetLRTD | avgt | 5 | 4184284.298 | ± 7651435.011 | ns/op |

| classic2DArrayGetTDLR | avgt | 5 | 389369.258 | ± 4064.665 | ns/op |

Amazon Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2676 v3 @ 2.40GHz

Wow, 10x as fast! Exactly what simondev found (using javascript). And what my laptop annoyingly failed to reproduce. There the difference was around a factor of 2.

Caveat: The individual numbers don’t mean that much.

Another thing that Kabutz says is that it pays off to simulate multidimensional arrays using a one-dimensional one. This is easy to do. But is it useful?

| Benchmark | Mode | Cnt | Score | Error | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seqMultArrayGetLRTD | avgt | 5 | 1399817.940 | ± 271516.298 | ns/op |

| seqMultArrayGetTDLR | avgt | 5 | 392543.679 | ± 3671.543 | ns/op |

The code for this benchmark (see github in the link at the bottom) allows any dimensions. Surely we can do a little better with a specialised version for just two.

Like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public int get(int row, int col) {

return data[row * this.cols + col];

}

public void set(int row, int col, int val) {

data[row * this.cols + col] = val;

}

| Benchmark | Mode | Cnt | Score | Error | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seq2DArrayGetLRTD | avgt | 5 | 1362950.693 | ± 43153.084 | ns/op |

| seq2DArrayGetTDLR | avgt | 5 | 390777.378 | ± 11339.226 | ns/op |

no difference!

So?

Ok, there is an advantage in calculating your own indexes, BUT only if you for some reason cannot benefit from caching. All TDLR scores are roughly equal. Suppose you are reading random parts of images, in that case, it helps.

What about writes?

| Benchmark | Mode | Cnt | Score | Error | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| classic2DArraySetLRTD | avgt | 5 | 4212263.046 | ± 267087.769 | ns/op |

| classic2DArraySetTDLR | avgt | 5 | 1032451.067 | ± 35040.403 | ns/op |

| seq2DArraySetLRTD | avgt | 5 | 2569007.766 | ± 45255.561 | ns/op |

| seq2DArraySetTDLR | avgt | 5 | 721699.703 | ± 22605.344 | ns/op |

3 to 4 times as fast for TDLR. Here index-calculation has more of an impact. So for editing random parts of images, especially for writing, use it.

–> But of course you should do your own measurements before embarking on any specific approach.

compiler blackholes

How to avoid dead code elimination with JMH?

- add a return parameter (like in the code example above)

- use compiler blackholes (as of jdk-17)

Not using the return parameter in a benchmark makes the JIT compiler think it can help you by removing your precious code. Adding a sensible return parameter prohibits it from being that clever. JMH will pick up whatever is returned and drops it into a black hole, and the information is lost. This in itself has some performance overhead and when the benchmark duration is in the same range, this will interfere with your measurements. Sounds like quantum physics, doesn’t it?

So Compiler blackholes make sure that the JMH Blackhole is optimized away, but NOT your benchmark code. This is new a JVM feature that you have to enable as follows:

java -Djmh.blackhole.mode=COMPILER -jar benchmark.jar

Old School?

Returning to the start of this article? Are arrays irrelevant for most developers, building boring web applications? They won’t often use them, but their JVM will, as arrays are used in String, ArrayList, and HashMap, in other words, the most prevalent classes (number of instances) in any running JVM.

So iterating the characters in a String or the elements in an ArrayList follows the same performance laws as those for arrays. Oh, and don’t use LinkedList. Practice differs from theory here, because of CPU caching. Most of the internet is still not aware of this, judging from a recent poll on LinkedIn. This video with Bjarne Stroustrup explains exactly why.

DIY

1

2

3

git clone https://github.com/shautvast/arraybench

mvn clean package

java -Djmh.blackhole.mode=COMPILER -jar target/benchmark.jar